EmpathyNet

A Green Paper

A green paper typically refers to a draft or tentative proposal with the intention of facilitating consultation and discussion.

The EthicsNet Guardians’ Challenge aims to enable kinder machines.

The Challenge seeks ideas on how to create the best possible set of examples of prosocial behaviour for AI to learn from (i.e. a machine learning dataset).

We welcome entrepreneurs, researchers, scientists, students, and anyone eager to contribute, to jump into this challenge and to help propose a solution.

Problem Excerpt from EthicsNet Guardians’ Challenge.

Jimmy looked at Robutt, who was squeaking again, a very low, slow squeak, that seemed frightened. Jimmy held out his arms and Robutt was in them in one bound. Jimmy said, ‘What will the difference be between Robutt and the dog?’

‘It’s hard to explain,’ said Mr Anderson, ‘but it will be easy to see. The dog will really love you. Robutt is just adjusted to act as though it loves you.’

‘But, Dad, we don’t know what’s inside the dog, or what his feelings are. Maybe it’s just acting, too.’

Mr Anderson frowned. ‘Jimmy, you’ll know the difference when you experience the love of a living thing.’

Jimmy held Robutt tightly. He was frowning, too, and the desperate look on his face meant that he wouldn’t change his mind. He said, ‘But what’s the difference how they act? How about how I feel? I love Robutt and that’s what counts.’

And the little robot-mutt, which had never been held so tightly in all its existence, squeaked high and rapid squeaks - happy squeaks.

A Boy’s Best Friend (Asimov, 1975).

Contents

1 EmpathyNet

Sir said, ‘These are amazing productions, Andrew.’

Andrew said, ‘I enjoy doing them, Sir.’

‘Enjoy?’

‘It makes the circuits of my brain somehow flow more easily. I have heard you use the word “enjoy” and the way you use it fits the way I feel. I enjoy doing them, Sir.’

Andrew demonstrating empathy in The Bicentennial Man (Asimov, 1976).

In this green paper, we introduce EmpathyNet - a multimodal dataset that serves as the foundation for learning empathy.

We are conscious that the original problem statement from the EthicsNet Guardians’ Challenge called for

[…] ideas on how to create the best possible set of examples of prosocial behaviour for AI to learn from (i.e. a machine learning dataset).

However, after much deliberation, we offer a counterproposal to instead design a dataset that assesses demonstrations of empathy. Here we describe some of our motivation behind this counterproposal. For more details please refer to Sections 3 and 4.

In the context of ethics, empathy serves the dual purpose of motivation and teacher. Empathy motivates the formation of rules such as:

Do unto others as you would have them do unto you.

Rules such as these partly originate from our empathy and identification with fellow humans and organisms.

Empathy also teaches. Humans infer the likability or normalcy of their actions from the responses of the people around them. For instance, children may infer that sharing is good from positive vibes given by their peers and parents. Such vibes include verbal language, tone of voice, body language and facial expression - with latter factors contributing more when verbal comprehension is inadequate. The ability to understand such vibes stem from empathy, which we define here as:

The ability to recognize, understand and share the feelings and thoughts of another.

Other animals, such as dogs and cats, have also exhibited empathy. Examples include the importance of tone of voice in training animals and the concept of emotional support animals. This illustrates two important points.

- The language barrier is near-unbreachable between humans and other animals. Yet both parties are able to convey subtle emotional messages, ranging from sadness to anger to happiness. This might indicate that textual information is unnecessary for empathy, with a greater emphasis on body language, tone of voice and facial expression.

- As humans we do not know for sure if our animal companions truly empathize with us. Do they really know how our emotions feel like? Do they really understand and share our feelings? Without a device for transplanting consciousness, we will probably never find out. Yet many humans firmly believe that animals truly empathize, based on our inference from superficial cues. This suggests that for artificial intelligence, demonstrating empathy might be far more crucial than truly possessing empathy.

There is no right to deny freedom to any object with a mind advanced enough to grasp the concept and desire the state.

Judge’s decision in The Bicentennial Man (Asimov, 1976).Based on these observations, the goal of EmpathyNet is to facilitate the assessment of demonstrations of empathy. We adopt the term ‘demonstrations of empathy’ to indicate that we are concerned about outward manifestations of empathy such as recognition and generation of cues (see below). This is primarily because assessing true underlying empathy seems to be a debatable and intractable notion. Also, as mentioned above, demonstrating empathy might be far more crucial (and tractable) than provably possessing empathy.

The heart of EmpathyNet is a multimodal dataset of cues, which we define here as:

A signal that conveys a feeling or thought.

Cues can take the form of:

- Verbal messages. The textual content of speech.

- Audio cues. The tone, speed and manner of speech or non-speech sounds such as crying and laughter.

- Facial expressions. Facial movements and distortions.

- Body language. Body posture, tics, gestures and their associated characteristics such as size and speed.

We then assess demonstrations of empathy by a series of tasks involving recognition and generation of cues. Specifically, the dataset comprises cue groups, where a cue group contains a video/image (facial expression or body language) cue, with corresponding audio and text (verbal) cues.

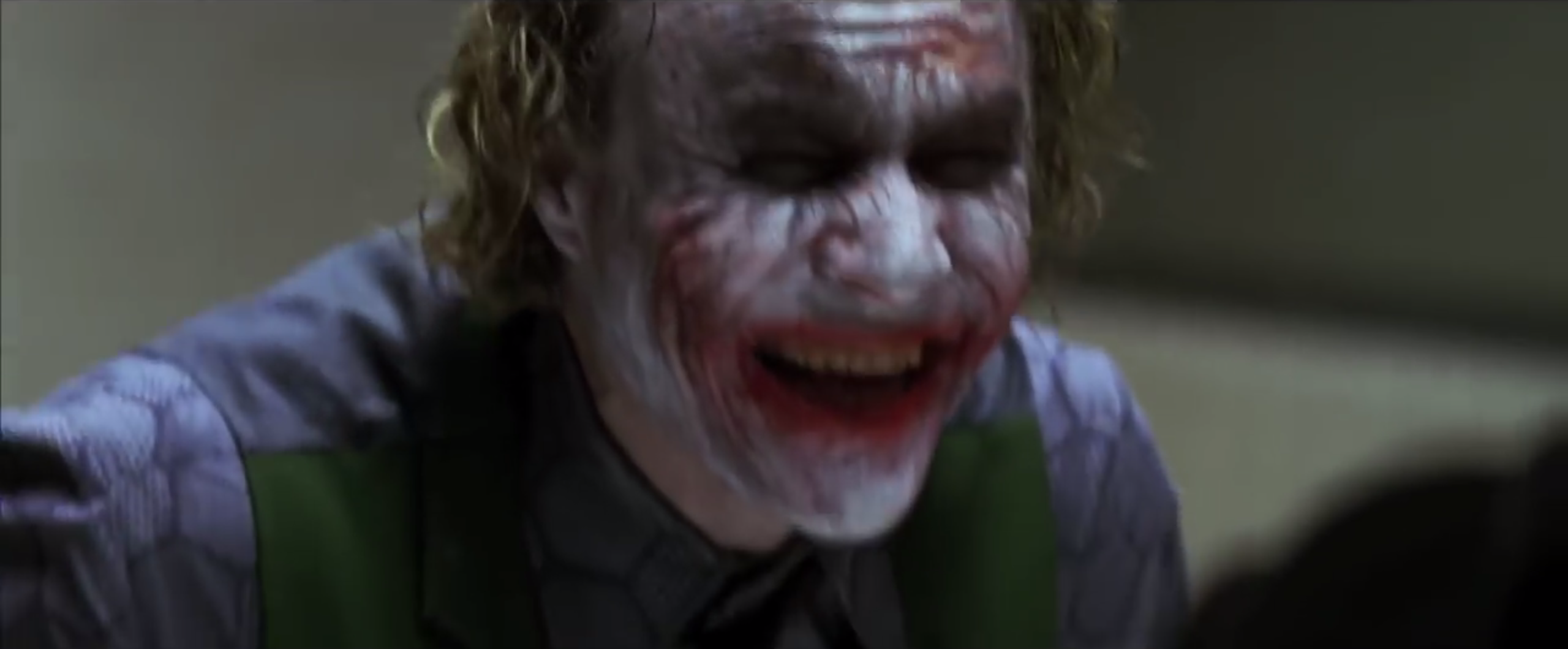

Example of a set of cues. (The Dark Knight, 2008)

| Cue Type | Value |

|---|---|

| Video | |

| Audio | Refer to Video |

| Image |  |

| Text | *Laughter* I don't wanna kill you! |

The irony of using Joker in an ethics dataset!

In the example above, the video of a face is paired with a corresponding screen capture of the expression, audio clip and subtitle. As the example hints, existing movies, documentaries and video platforms might be a tremendous source of data.

Important Note: For several reasons (see Section 5), we might want to remove textual information from audio cues. This can be done by applying a form of blurring to the audio cues, so only nontextual information, such as pitch and speed, is retained, while the exact words are unintelligible.

Several tasks can then be conceived, grouped under classification and generation.

- Regular Classification. Label the cue as belonging to one of several predefined classes. This would be similar to ImageNet, but in this case the classes could be forms of social expressions or emotions such as sadness, anger, happiness, madness (above). We can choose to classify a set of cues (video+audio+text), classify single video/audio/text cues individually or a mixture of both.

- Multiple-Choice-Question (MCQ) Classification. Predict the correct A cue out of N options, conditioned on a B cue. Eg. given the image cue from the above example, predict the most likely corresponding text cue out of four possible choices.

- Generation. Minimize the negative log likelihood (NLL) of an A cue, conditioned on a B cue. Eg. given an image cue, maximize the probability of generating the corresponding text cue. NLL is a metric used commonly in assessing generative models, such as in the work by van den Oord et al. (2016) (see Tables 1 and 2 in the paper).

For all three tasks, several tasks can be conceived by mixing the types of cues used, such as predicting the most likely audio cue based on an image+text cue or predicting the most likely image cue based on an audio cue etc.

In the following sections, we first analyze how to build a successful dataset (Section 2), before a brief discussion of ethics (Section 3). These discussions serve as a foundation for introducing the motivations behind EmpathyNet (Section 4). Finally, we elaborate on implementation details in Section 5.

2 On Datasets

EthicsNet is modeled after ImageNet, a dataset for machine vision which has been instrumental not only in providing actionable data for new machine vision algorithms to use, but also in providing a rallying-point and benchmarking tool for rapid development within this space.

Excerpt from EthicsNet Guardians’ Challenge.

In this section, we first analyze the success of ImageNet (Deng et al., 2009), the popular image dataset consisting over 14 million annotated URLs of images. This is meant to derive a set of possible guidelines for building a successful dataset. Next we discuss some alternative dataset concepts that we have considered and rejected, before conceiving EmpathyNet.

Success Factors of ImageNet

- Size matters. The size of ImageNet is obviously an important factor in the success of image classification. On a side note, the size of ImageNet has also made it a target for solving the problem of efficiently training on large datasets.

- Annotation agreement. This refers how much two (or more) separate human annotators agree on the same labels for a set of given samples. Without good annotation agreement, a large dataset annotated by many humans is likely to be extremely noisy with differing opinions on the meaning of labels. The resulting models trained on such noisy datasets will also suffer in performance. This also leads to unconvincing metrics (see below), since accuracy is meaningless on a dataset with poor annotation agreement. In the case of EthicsNet, the subjective nature of ethics makes annotation agreement a significant challenge.

- Specific scope. Despite its size, ImageNet is a rather specific dataset with an arguably narrow scope. Every sample is labeled with one of a thousand labels (1000 in the annual challenge; the actual ImageNet has over 20 000). One thousand classes sounds like a huge number but is tiny compared to the number of objects a human sees everyday. Furthermore, the dataset consists of only images ie. 2D representations. In limiting the dataset with such clear constraints, the image classification task becomes far more tractable and success of models can be measured concretely.

- Well-defined metrics. ImageNet, being primarily a classification task, has a simple metric of accuracy. The actual metrics may be more elaborate, such as top-five-accuracy, but these remain easily measured and understood. The clarity of the metric is paramount since it defines the task and provides a goal for researchers to work towards.

- Reuseable for other tasks. While it originated as a classification dataset, ImageNet has also served as the foundation for a wider variety of tasks, such as object (bounding box) detection and image generation (minimize negative log likelihood).

On a side note, this insightful Quartz (Gershgorn, 2017) article touches on several other important factors that have led to this success, such as the collaboration with PASCAL VOC and the AlexNet entry in 2012.

Possible Alternatives to EmpathyNet

In evolving the concept of EmpathyNet, we have considered a few other possibilities. Ultimately we have chosen to propose EmpathyNet, but we list some possibilities here to serve as inspiration and provide more food for thought.

EthicalText

Humans are able to read a piece of short text and decide if the text is describing ethical behavior eg.

Shelter provides dogs with big comfy chairs.

Taken from r/MadeMeSmile.

We might test for such ethical reasoning with a dataset of text samples, where each sample has a binary label indicating if the text is describing ethical behavior or concepts. (The label could also be a discrete or continuous score.) A low-cost way to do this is to crawl sites such as the r/MadeMeSmile or r/UpliftingNews subreddits and extract post titles, marking them as ethical. Neutral samples can be obtained from regular subreddits eg. r/Showerthoughts or r/puns. Nonethical samples can be obtained from subreddits such as r/UnethicalLifeProTips or r/assholedesign.

Drawbacks. Even if a model performs well on such a task, we might consider it a text classifier rather than having learned any semblance of ethics. A successful model might be similar to a spam classifier, just in a different domain. Such a model is also probably inherently brittle, unable to accurately classify text with unseen vocabulary. Also, ethics feels inherently multimodal, not just correlated with certain word frequencies or sequences. One way to think about it - replace every word in the vocabulary of the dataset with a random word eg. replace help with giraffe. The model will still be able to perform equally well, which feels counterintuitive.

SimsNet V1

The Sims franchise is a readily available simulation environment with human characters. Using a Sims game or a similar environment, we can set up certain scenarios and allow the machine to control a single character. This can be in the form of reinforcement learning eg. the machine controls the character and then tries to maximize a certain utility score. This can also be in the form of a regular dataset eg. with machine predicting the best immediate action to take in a single scenario, out of four options. Such a dataset appeals to a more language-independent concept of ethics, beyond textual constraints.

Drawbacks. Such a dataset is actually essentially the same as any game environment eg. Arcade Learning Environment (Bellemare et al., 2013) or OpenAI’s Gym (Brockman et al., 2016) and Gym Retro (Nichol et al., 2018), where an agent takes actions in an environment and maximizes a score. Designing a model the chooses the best action for maximizing a score is the goal of reinforcement learning. Instead, the more important problem in the context of ethics is

How can we design a reward function that maximizes ethical behavior?

(see Section 3).

SimsNet V2

In natural language processing, there is a concept known as language modeling. For instance, given the entire Shakespeare corpus, we can train a model to predict the next word, conditioned on the previous five words. Interestingly, researchers have extended this concept to show that trained models demonstrate some semblance of understanding and even commonsense reasoning (Trinh & Le, 2018) (Radford et al., 2018). In a similar manner, there might be a dataset containing scenarios (ie. sequences of actions) demonstrating ethical behavior. A model could be trained to predict the next action given previous context, thereby learning a model of ethical behavior.

Drawbacks. One consideration is that the input provided to the model should be a form of API for the Sims-like environment (eg. a set of discrete actions) rather than pixel values of the image or video. It will be challenging, in terms of resources, for a model to have to generate entire images for predictions. Such an obstacle distracts from the true goal of EthicsNet. Since we are constrained to having some form of API for the action space, we cannot use cheaper alternatives such as clips from movies and videos.

Finally, context is a significant factor in making ethical decisions. We will have to consider how to embed contextual information into the samples. For example, if the scenario is Alfred hitting Bob, the context might be self-defense or robbery or playful banter, with the ethicality varying widely based on the context. How might we embed such contextual information without straightforwardly disclosing the answer (ie. whether it is ethical behavior)? It will also be challenging to provide context for each sample in an efficient effective manner that is scaleable for the EthicsNet organizers.

3 On Ethics

The primary purpose of this section is to discuss factors underlying ethical behavior, in order to shed light on how we can motivate AI to adopt such ethical behavior.

Ethical Behavior as Utility-maximizing Behavior

In ethical conundrums such as the trolley problem, utility-maximization is an important motivation in ethical decisions. For instance, if forced to make a decision, assuming all humans are equal, killing one human is better than killing two humans since we should maximize utility. In reality, utility maximization is a fluffy notion, with a host of difficult questions that must be answered:

- How do we define utility?

- How do we measure or infer utility based only on superficial observations?

- How do we tradeoff short-term and long-term utility?

- How do we perform utility algebra? (eg. killing a baby for any amount of money is unethical, yet it cannot be said that a baby’s life is worth infinite value, especially when we compare it to another human)

These are important intractable questions yet humans are arguably able to make and use an estimation/inference of local utility/score in order to make somewhat ethical decisions. As humans, we recognize that everyone’s concept of ethics and utility is mostly unique, subjective and self-derived. What is important for societal stability is that:

- Most of our values are aligned

- Minor misalignments are compromised

- Major misalignments are debated and reduced to points 1 or 2

A huge contributing factor to the relative success of the above approach is a human’s ability to infer utility-related consequences of their actions, based on the cues of those around them. Accidentally pushing someone might cause mild annoyed responses, while deliberately punching someone might incite more violent responses. The resulting utility of the two actions can be inferred from the responses. A similar case can be made for dogs, cats and other animals, which are trained and tamed using similar cues. Therefore, a step towards building ethical AI could be to train AI to recognize and generate such behavioral cues and expressions, such that they can be used to infer utility or an innate reward function.

Ethical Behavior as Empathetic Behavior

Whatever is hurtful to you, do not do to any other person.

Do unto others as you would have them do unto you.

Many ethical rules can be traced back to the guidelines above, which are grounded in empathy. For example, lying is unethical partly because we do not want to be lied to. Empathy also relates to the previous interpretation of ethical behavior, since empathy is required for humans to effectively interpret supervisory signals from behavioral cues.

When you see someone crying, you might empathize by placing yourself in their shoes and recognizing that you feel sad. This recognition comes about because we associate crying with sadness. Hence empathy might be founded on the ability of humans to both recognize and demonstrate outward manifestations of inner emotions and thoughts. As such, we have the recurrent theme of the importance of recognizing and generating social cues.

Ethical Behavior as Normal Behavior

Interestingly, humans often ignore ethical values that originate from previous discussions of utility-maximization and empathy. As a simple example, jaywalking is unethical because it compromises on the utility of the entire society and if we empathize with drivers, jaywalking is undesirable and dangerous. Yet despite such considerations, jaywalking is blatantly common.

In such cases, unethical actions, as defined by previous contexts, may become ‘ethical’ because they are performed by a majority of humans around us. Such behavior is normalized and it may be antisocial to go against such norms.

It is important for AI to be able to learn these norms and this inferring if a decision/action is approved/disapproved/disregarded. Again, such inferences have to be made based on recognizing behavioral cues. Furthermore, the AI has to demonstrate compliance with such norms by generating and manifesting appropriate cues eg. choosing to express disdain or disregard for jaywalking. Once again, we see the importance of recognizing and generating these social cues.

4 Why EmpathyNet?

The primary motivation behind EmpathyNet is the importance of recognizing and generating social cues, in the context of ethics (see Section 3). A model that does well on EmpathyNet will be able to match facial, behavioral, audio and textual cues. This capability serves as a foundation for pro-social and ethical behavior.

For instance, Section 2 mentioned that an important problem in designing ethical AI is designing a suitable reward function that maximizes human-aligned ethical behavior. A model that is equipped with the ability to recognize human cues might be better equipped to infer the underlying reward function of observed humans. For example, a robot that bumps into a human while walking might observe her expression of annoyance and realize that bumping into people is impolite. Recognizing this expression of annoyance and matching it to other cues experienced before will be an important first step towards learning a suitable reward function.

Furthermore, a huge part of communicating empathy is the ability to demonstrate these cues. EmpathyNet, as a dataset of cues, potentially enables models to generate corresponding cues that will allow them to demonstrate empathy.

We might ask, “Do machines that recognize and demonstrate empathy truly understand empathy?” But we would like to point out that such questions are intractable and irrelevant. As mentioned in Section 1, we do not know for sure if animals understand our feelings, yet we believe they do because they seem to recognize our feelings and demonstrate behavior that convey their own feelings. Demonstrating empathy might be far more crucial than truly possessing empathy.

There are also several other advantages of EmpathyNet, which we list below.

Multimodal. Compared to purely textual or purely image-based datasets, EmpathyNet is multimodal, which seems suitable in the context of ethics.

Inclusive. If we gather the data for EmpathyNet using movies, documentaries and videos from online platforms (see Section 5), then there is a good chance that the dataset is inclusive across races, nationalities and age groups.

Cost Effective. Using the method described below, it is possible to generate a large amount of data with relatively low human cost. Furthermore, the data is not ethics-specific and can be used by researchers for other current and future tasks. If the above factors of multimodality and inclusiveness are observed, this dataset might also go a long way towards reducing algorithmic bias in image and audio models.

Simpler Annotation Agreement. In Section 2, we mentioned that annotation agreement is a significant challenge for creating an ethics dataset. With EmpathyNet, we sidestep this challenge, since the dataset primarily deals with recognizing and generating social cues, as opposed to deciding if a decision/action is ethical or not. In many ways, the annotation agreement problem is simpler for classifying and matching social cues, as compared to ethical judgements.

5 Building EmpathyNet

As hinted in earlier sections, a low-cost method of gathering data for EmpathyNet is through movies, documentaries and online video platforms. There may be potential collaboration with Google/YouTube or movie studios to use their collections. Here we describe a potential efficient manner to collect EmpathyNet data.

Collecting the Data

Consider if we have a single movie, containing video, audio and textual (subtitles) information. We also begin by focusing on facial expressions rather than the entire set of body language cues.

We first use a face recognition model to identify segments of the movie with large enough faces (eg. more than 20% of the screen dimensions). We then cut out these video and audio segments, ensuring that the sentences in the subtitles are kept whole and uninterrupted. Each segment should only contain a single speaker. We now have samples of matched video, audio and textual cues. We can also use screen captures of the video segments (eg. 5 screen captures taken at equal intervals in each video segment). This will provide a static image alternative for facial cues, which will be easier for researchers to process.

Another post-processing step we can perform is to remove textual information from the audio. One way is to perform blurring on the audio, such that the tone and speed are retained while the words are unintelligible. This is to prevent models from trivially matching lip movements to audio or matching text to audio., since we do not want to test for lip-reading or speech-to-text capabilities.

Designing the Tasks

The above steps might suffice for a dataset meant to train generative models. However, for classification tasks, we still need labels.

For a regular classification task like the ImageNet challenge, each sample (either a group of corresponding cues or a single cue) will belong to one of several predefined classes. We will have to examine the actual dataset that we have collected in order to determine suitable classes.

For a multiple-choice-question (MCQ) task like DeepMind’s Procedurally Generated Matrices (Barrett et al., 2018), we need to generate questions.

Suppose the task consists of choosing the correct audio cue for a given image cue (above). A question consists a single image cue with four audio cues, one of which is correct. From the previous process, we already have a dataset of matched cues ie. correct answers. For every sample, we will have to add three other samples that serve as the incorrect answers. These incorrect options can be randomly sampled from other samples in the dataset, but there are a few potential pitfalls here.

- All the audio cues for a single question should have similar characteristics eg. gender and age. Otherwise, the model might be matching an image cue of a child to the audio cue of a child because it has learned about age correlation rather than expression correlation.

- We also have to be careful not to add another audio cue that is from a similar class. For instance, consider an image of an angry man with a corresponding audio cue of him shouting. We can generate incorrect audio cue options by randomly picking audio cues from other samples. But if the randomly selected audio cue is also from another angry man, it should technically be a correct answer as well. So we have to be careful and sample from different classes for incorrect answers. This could be easily facilitated if we already determined a fixed set of predefined classes.

- Finally, as mentioned above, removing textual information from the audio is important since we do not want a lip-reading or speech-to-text model.

6 Conclusion

In considering how to communicate ethical values to artificial intelligence, it might be worth taking a step back and observing how we communicate and understand each other across language barriers and even species barriers. Expressions, body language and sounds cut across language barriers and species barriers to enable communication and coexistence. A dataset for matching expressions, body language and tone of voice, has tremendous potential for assessing empathy and other fascinating goals, such as helping machines communicate with humans.

EmpathyNet does not seek to solve EthicsNet’s vision of creating a dataset to teach AI ethical behavior. Rather, EmpathyNet seeks to be a small step towards fulfilling that vision, by proposing a dataset and a set of tasks that give a specific, tractable and measurable challenge.

7 References

Asimov, Isaac. A Boy’s Best Friend. Boys’ Life, 1975. Print.

Asimov, Isaac. The Bicentennial Man. Random House, Inc., 1976. Print.

Barrett, David GT, et al. “Measuring abstract reasoning in neural networks.” arXiv preprint arXiv:1807.04225 (2018).

Bellemare, Marc G., et al. “The arcade learning environment: An evaluation platform for general agents.” Journal of Artificial Intelligence Research 47 (2013): 253-279.

Brockman, Greg, et al. “Openai gym.” arXiv preprint arXiv:1606.01540 (2016).

Deng, Jia, et al. “Imagenet: A large-scale hierarchical image database.” Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2009. CVPR 2009. IEEE Conference on. Ieee, 2009.

Gershgorn, Dave. “The data that transformed AI research—and possibly the world”. Quartz, Quartz, 26 July 2017, https://qz.com/1034972/the-data-that-changed-the-direction-of-ai-research-and-possibly-the-world/.

Nichol, Alex, et al. “Gotta Learn Fast: A New Benchmark for Generalization in RL.” arXiv preprint arXiv:1804.03720 (2018).

Radford, Alec, et al. “Improving language understanding by generative pre-training.” (2018).

The Dark Knight. Dir. Christopher Nolan. Perf. Christian Bale, Heath Ledger, and Aaron Eckhart. Warner Bros., 2008.

Trinh, Trieu H., and Quoc V. Le. “A Simple Method for Commonsense Reasoning.” arXiv preprint arXiv:1806.02847 (2018).

van den Oord, Aaron, et al. “Conditional image generation with pixelcnn decoders.” Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems. 2016.

I don’t know what he feels inside but I don’t know what you feel inside. When you talk to him you’ll find he reacts to the various abstractions as you and I do, and what else counts? If someone else’s reactions are like your own, what more can you ask for?

Little Miss defending Andrew, from The Bicentennial Man (Asimov, 1976).